The previous article in this series provides guidelines for developing a business partnership with your parenting partner. That is, a relationship that is based on logic rather than emotion. In this article we’ll explore the biggest obstacle to this: anger.

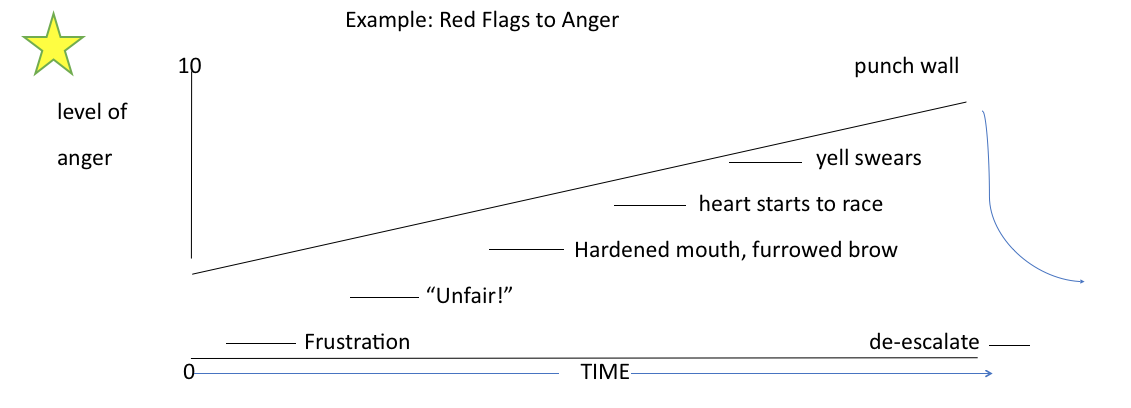

There are many levels of anger: annoyance, irritability, anger, fury, rage, etc. It’s important to notice when you are getting increasingly angry and you are headed towards a rage explosion (whatever that looks like for you), because there is collateral damage that happens along the way – most importantly, to your children. So the sooner you notice you are on this trajectory the sooner you can stop yourself, change course, and do something that will help your children rather than harm them.

To manage your anger effectively you first need to know your red flags. Red flags are signs and symptoms that let us know we are creeping up that anger scale. Except for Emotional Red Flags, a red flag is something that is typically present when we’re escalating in anger and doesn’t tend to be there when we’re feeling other things. There are four types of red flags:

- Behavioral: things you do that others can probably see

Examples: clenching fists, pacing, rolling eyes, yelling, slamming doors, etc. - Physiological: symptoms that your body creates

Examples: face turning red, racing heart, muscular tension, etc. - Cognitive: your thoughts

Examples: “This is so unfair!” “Why do they always do this?!” - Emotional: other feelings that precede angry ones

Examples: frustration, anxiety, embarrassment, guilt, shame, hurt, etc.

The graph above illustrates how this person experiences anger over time (regardless of the length of time it takes to hit the apex). That curved line after the big blow up (“punch wall”) is when they suddenly figure out they’re angry and need to de-escalate. It’s good to realize this after punching the wall, but imagine if they’d thought of it sooner? All the stuff that came before wouldn’t have happened and done damage. What if they began to de-escalate as soon as they noticed themselves feeling frustrated and thinking “unfair!”? They could take a time-out and cool down before they wasted more time in anger and blew up in front of their parenting partner and children. Win-win-win. When you notice yourself getting angry, take a time-out and cool down (if it’s good enough for our kids, it’s good enough for us, right?). If you are talking with the other parent, say: “I need a break from this discussion. I’ll contact you later today/tomorrow so we can finish talking about this.” And then contact them when you promised. While you are taking your break, distract yourself first to get some distance from the event, thoughts, and emotions, and then consider where they might be coming from. When you’ve been able to empathize or at least get better control of yourself, return to the discussion as promised and ask if they would like to start or would like for you to start. That can help decrease the anxiety and anger on their part which sets the stage for a more productive and less emotional discussion.

Now, about anxiety and anger… have you ever noticed they often go hand in hand? That’s because anger is often a secondary emotion to more vulnerable emotions, like anxiety, guilt, shame, fear, embarrassment, sadness, or hurt. People, especially men, are taught in this culture that anger is more acceptable than a vulnerable emotion because it is perceived as strong. So we learn to show anger rather than a “softer” and more authentic emotion. But imagine how a conversation might go differently if both parents were willing to show their genuine, vulnerable emotions with each other rather than just show the anger? It not only decreases the reaction of fear and defensiveness but it allows us to express and understand the actual problem (“I’m worried she won’t get a good education in that school system”) rather than just issue an attack (“She’ll go to that school over my dead body!”).

The point here is to be authentic, not to be passive. Passive communication is where you don’t stand up for your rights and so you don’t tend to get your needs met (e.g. letting the other parent choose the babysitter against your better judgment). Assertive communication is where you stand up for your rights while respecting the rights of others (“Because of (x reason) I’m concerned this babysitter isn’t very responsible and I want to find a new one”). Aggressive communication is where you stand up for your rights while disrespecting others (“You are a big idiot if you think I’m going to let that imbecile take care of my child!”). Passive-aggressive communication is where you are indirectly aggressive (“The babysitter you chose is indeed very attractive but I believe other qualities are more important when it comes to taking good care of our child so I’ll pick the next one”). Assertiveness is the only direct form of communication; the rest are indirect and leave a lot to the interpretation of the other person. When a person relies primarily on passive communication, they will eventually have a blow-up later; either aggressive, passive-aggressive, or a “blow-in” of depression.

The next article will deal with how to express anger, how to use it to your advantage, and the relationship between thoughts and anger.